What a Dangerous Place You’re Sitting in!

Kynan Sutherland Sensei

What a Dangerous Place You’re Sitting In!

Kynan Sutherland Sensei (2018)

The name of tonight’s talk is, “What a dangerous place you’re sitting in!”

These words come from the collection of koans called Entangling Vines. Here is the case in full [Case 215]:

Bai Juyi, the provincial governor, said to the priest Niaoke Daolin, “What a dangerous place you’re sitting in!”

“What danger am I in?” said [the priest]. “The governor’s danger is far greater.”

“I govern this land,” said [the governor]. “What danger could I be in?”

[The priest] answered, “Passions burn, the intellect never rests. What could be more dangerous than that?”

The governor asked, “What is the central teaching of the Buddha Dharma?”

[the priest] replied, “As for doing evil, avoid it; as for the good, practice sharing it.”

“Even a three year old child could have told me that,” responded the governor.

“Even a three year old child can say it, but even an eighty-year-old cannot practice it,” said [the priest].

[the governor] bowed and departed.

[Entangling Vines, Case 215]

So – what a dangerous place you’re sitting in!

It might not look like it right now, seated as we are in this architecturally designed house with homemade detergent and knitted dishcloths, but this very breath could very well be the last you ever take. And perhaps we should even get rid of the word “could,” because this breath is the last breath you will ever take, the last great breath we share with all the many beings.

I’m sure I’m not alone in this room when I express my anxiety about the sprawling dangers of our time: the rise of strongman politics, the spread of degrading social media, our global refugee crisis, the accelerating rate of environmental collapse... It’s all terrifying, sickening, and has a momentum that feels, well, unstoppable.

But this is where we find ourselves, this is where we sit, right on the point of this needle. So tonight I want to ask, how does Zen respond to the dangers of our time? Is it possible to take refuge in this danger? And might this draw us back into something like shared reality?

*

In the koan I just mentioned we meet two very different characters. First, we have Bai Juyi, the governor. Second, we have Niaoke Daolin, the priest. Immediately there’s a clash of values: the political meets the non-political, the profane meets the sacred, the spiritual meets the worldly. Something interesting is bound to happen!

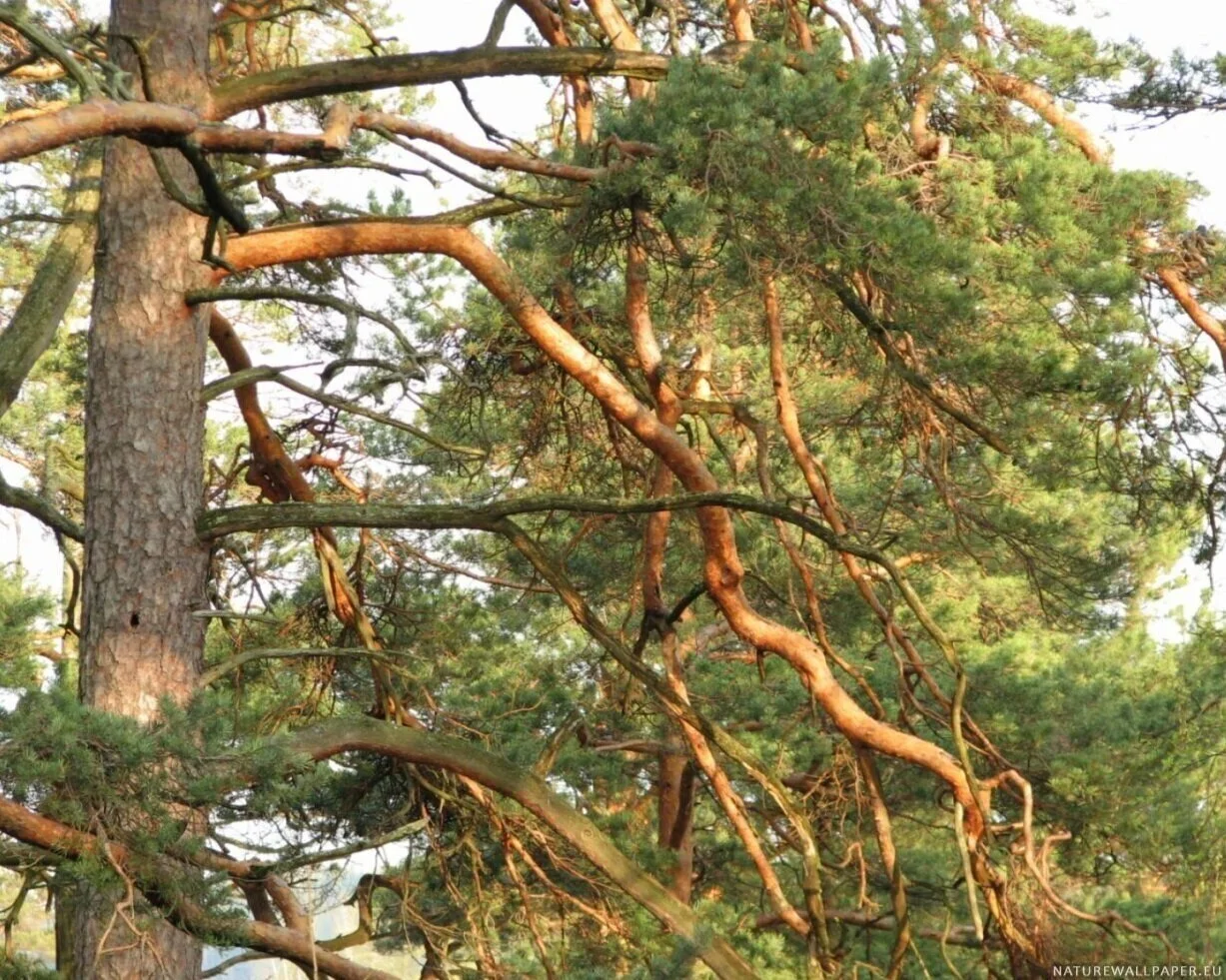

The priest, Niaoke Daolin, was famous for shunning his temple at Zhouwang si and sitting in a large pine tree. Instead of practicing with the other monks in the dojo he preferred to perch on a swaying branch, bobbing up and down with the breeze. Now that’s rustic! Indeed, Niaoke’s name is actually a nickname, and translates as “Bird’s Nest.”

Bai Juyi, on the other hand, was not only one of China’s highest ranking officials and a governer, but one of China’s most famous poets (you might know Arthur Waley’s translations of his poems, where he is known as Po-chu’i). So Bai Juyi was no stranger to public life with all its perks and perils. He was even elected to the become “President of the Board of War” in 841 by the emperor. Not someone to be crossed lightly!

The conversation begins with Bai Juyi strolling right up to Niaoke and saying, “What a dangerous place you’re sitting in!” Indeed, there’s nothing more dangerous than being perched on a pine branch, unless of course you lie down in a crocodile’s nest or fall asleep in a swimming pool. But Bai Juyi may be commenting on Niaoke’s economic vulnerability too. Monks and monasteries relied on state support in those days, and had no weapons or defences to protect them from wars. Buddhism in those days was very exposed.

Either way, Niaoke is unfazed by Bai Juyi’s comment and says, “What danger am I in? The governor’s danger is far greater.”

The governor responds in a defensive way: “What danger could I be in? I govern this whole land!”

You know the type. So often leaders, particularly political ones, think they’re protected by their rank, wealth and influence. They might even believe they’re fortified from fate, as if to say, “I rule this place! I’m in control! So what could ever happen to me?”

Niaoke doesn’t flinch. With calm curiosity he replies, “Passions burn, the intellect never rests. What could be more dangerous than that?”

This is true danger. Alive and real in every one of us. Danger is our ground. It’s where we live. The word danger is intimately linked to the word “feel,”" from the latin periculum. So in this sense simply to feel is dangerous. “Experience” too comes from the latin expirere, which means to undergo, endure, suffer.

So life is suffering, just as the buddha said. To open yourself up to this suffering is to risk being touched by suffering in return. But this, ironically, is what dissolves suffering. Remember Shakyamuni touching the earth to affirm his own awakening? At that moment the earth touched him, and there was no Shakyamuni, no earth, only this [reaching down and touching the earth.]

Zazen is dangerous in just this way. We’re not here to distance ourselves from the world, or protect ourselves from it. Zazen isn’t about cooling the passions or numbing the intellect. No – we’re here to experience the true nature of our passions and intellect, all of which “never rest” as Niaoke observes. Passions and the intellect are expressions of our true nature, our endlessly shared reality.

The governor is intrigued. He intuits something in Niaoke’s words and hesitates. He then asks a very different kind of question, something quieter and more humble: “What is the central teaching of the Buddha Dharma?”

It’s almost like a plea, a genuine cry from the heart, however testing. In response, Niaoke offers an exquisite teaching: “As for doing evil, avoid it; as for the good, practice sharing it.”

This is a distillation of the Three Pure Precepts, which we take up in our Jukai ceremony:

I vow to maintain the precepts.

I vow to practice all good dharmas.

I vow to save the many beings.

Evil isn’t a word that crops up very often in our tradition. But when it does turn up, it’s always worth looking at closely. So what does it mean to avoid doing evil?

*

I’ve recently been reading “Kolyma Tales” by Varlam Shalamov, who was arrested for an unknown “crime” in 1929 and then spent 17 years in the Siberian forced-labour camps of Kolyma. Over three million people died in those camps, and Shalamov records his own hellish experiences in lucid detail. Incredibly, he never defaults to self-pity or complaint. Rather, he records his day-to-day encounters and all the various things he did to survive, both physically and spiritually.

In the story Dominoes, for instance, we find Shalamov sick in the camp hospital. He’s pitiably weak and cannot stand, speak, or even think. The resident doctor, a man called Andrei Mihailovich, orders him to rest. The nurse is told he must be fed for two months and barred from work.

Slowly, very slowly, he recovers. One night he’s woken by a camp orderly with the words, “[The doctor] Andrei Mihailovich wants you…Kozlick will show you the way.”

Kozlick, another patient, leads Shalamov to the doctor’s room. Shalomov goes inside. “Feel like playing Dominoes?” asks the doctor. They sit down on the doctor’s clean bed (which Shalamov can’t help marvelling at—it’s so clean!), and is offered tea, bread, kasha – unheard of luxuries. “I had not seen sugar for several years,” Shalamov writes. “I felt warm.”

I’ll read you the last part of the story, after they have been playing and chatting for some time:

The game continued slowly. We were more concerned with telling each other our life histories. As a doctor, Andrei Mihailovich had never been in the general work gang at the mines and had only seen the mines as they were reflected in the human waste, cast out from the hospital or the morgue. I too was a by-product of the mine.?

“So you won,” Andrei Mihalovich said. “Congratulations. For a prize I present you with – this.” He took from the night table a plastic cigarette case. “You probably haven’t smoked for a long time?”

He tore off a piece of newspaper and rolled a cigarette. There’s nothing better than newspaper for homegrown tobacco. The traces of typographic ink not only don’t spoil the bouquet of the home-grown tobacco, but even heighten it in the best fashion. I touched a piece of paper to the glowing coals in the stove and lit up, greedily inhaling the nauseatingly sweet smoke.

It was really tough to lay your hands on tobacco, and I should have quit smoking long ago. But even though conditions were what might be called “appropriate”, I never did quit. It was terrible even to imagine that I could lose this single great convict joy.

“Good night,” Andrei Mihailovich said, smiling. “I was going to go to bed, but I wanted to play a game. I really appreciate it.”

I walked out of his room into the dark corridor and found someone standing in my path near the wall. I recognized Kozlick’s silhouette.

“It’s you. What are you doing here?”

“I wanted a smoke. Did he give you any?”

I was ashamed of my greed, ashamed that I had not thought of Kozlick or anyone else in the ward, that I had not brought them a butt, or a crust of bread, or a little kasha.

Kozlick had waited several hours in the dark corridor.

I love this story. And I think it gives an insight into avoiding evil.

When Shalamov says he is ashamed, I don’t hear self-pity in his words. His shame is more like courage. The courage to admit and stomach that shame: the shame that is born from even temporarily ignoring what is always a shared reality.

This is the courage of Purification. When we recite our sutras together we begin with the words, “All the harm and suffering ever created by me since of old…I now confess openly and fully.” Shalamov confesses in the same way—and this is what brings him into accord with others. Our ongoing practice is like this, awakening again and again to our flawed, yet flawless reality.

This is the dynamic of practice, where we return again and again to exactly where we find ourselves, where nothing and no-one is left out. It might be dangerous, can we call the wholeness of this fact anything but “good”?

If evil is a sort of blindness to shared life, as Shalamov indicates, then perhaps goodness is characterised by a willingness to admit shared life.

Shared life is clarity. It means being released from the tiny confines of our self-definition into the richness and radiance of each particular colour, sound, smell, taste, touch, thought. Here we are, never to be seen again! But this requires a subtle shift in our heart-mind, away from persistent self-obsession towards ongoing care for the many beings.

*

Recently my wife has been reading Anne Karenina by Leo Tolstoy. Every morning over breakfast I get a little update between packing the kids’ schoolbags and making lunches.

She’s nearly at the end and just the other day she came bouncing into the kitchen to tell me all about the character Levin. One of the farmhands on Levin’s estate has just told him that there is a difference between living for one’s own belly and living for the soul. Levin is dumbstruck. “Yes! Yes! Goodbye!” is all he can say:

Levin went in big strides along the main road, listening not so much to his thoughts (he still could not sort them out) as to the nature of his soul, which he had never experienced before…

He felt something new in his soul and delightedly probed the new thing, not knowing what it was.

Not-knowing is key here. Levin’s thoughts continue, but he doesn’t know anything about them. You get the sense that he doesn’t know who he is anymore, at least not in any conventional sense. And far from this being a destabilising thing, Levin finds this “not-knowing” to be the most fundamental and joyous thing he has ever experienced.

I and all people have only one firm, unquestionable and clear knowledge, and this knowledge cannot be explained by reason – it is outside it, and has no causes, and can have no consequences.

If the good has a cause, it is no longer good; if it has a consequence – a reward – it is also not the good. Therefore the good is outside the chain of cause and effect…

And I know it, and we all know it.

Can you hear his appreciation of shared reality here? I know it, and we all know it! Nothing and no-one is left out of this.

In fact, this is what Yunmen directs us to with his famous koan, “Every day is a good day.” Can we accept the goodness of muddled thoughts, physical ailments, lingering griefs, unexpected shocks? Can we resist trying to “know” or understand what is going on, and instead open ourselves up to experience what is happening without jumping to conclusions?

Issa expresses this beautifully in one of his haikus. He simply says,

A good world –

the dewdrops fall

by ones, by twos.

A good world.

I hope you can hear the deep, open hearted attention at play here.

I can just imagine him on the verandah, listening to the putt, puttputt, puttputt, putt of the drops falling from the eaves. I sense a wide, unbounded, unhurried, deeply attentive appreciation at work.

But clearly the poem isn’t just about literal dewdrops. It’s about our fleeting fears, joys, acquaintances, hopes. They all fall, here only for the briefest moment.

Indeed, all our losses, heartbreaks, the heartaches of our every day lives, fall—and are falling through us right now.

Can we savour them with the same wide, unbounded, unhurried appreciation that Issa demonstrates in this poem?

A good world –

the dewdrops fall

by ones, by twos.

The whole world falls. And the very falling is good.

And there is something marvellous about his final line, “by ones, by twos”. Indeed, in such a state of open attention, how can we draw dogmatic lines between things? Can we really say where one drop ends and another begins?

Indeed, can we really say where joy ends and sadness begins? Can we really say where sadness ends and joy begins?

By ones, by twos. Now pleased, now less pleased, now grumpy, now at ease. This is what we experience in zazen. In zazen we take the backwards step into our shared, natural, unhindered awareness. From there we can appreciate the full extent of our human condition—and realize that even the difficult aspects—searing grief, remorse, embarrassment, shame—are nonetheless good.

Because all of them are dewdrops. With their own particular colour, temperature, size and sound.

And where do they fall?

They fall into this: “a good world.”

*

So when Niakoe says, “As for the good, practice sharing it” he is inviting us to appreciate the constancy of the good.

The good that does not distinguish between good and bad. The fundamental good that is deeply at ease.

The governor, however, is still wary. He frowns a little and says dismissively, “Even a three year old child could have told me that!”

“Even a three year old child can say it,” replied the priest, “but even an eighty-year-old cannot practice it.”

How very true.

And notice that Niaoke isn’t just talking about any old eighty year old here. He’s talking about himself. And you. And me.

Can we really awaken to the good in the most disastrous situations? Can we genuinely include others even when they have slighted us, wronged us, abused us in some way.

It’s hard! It’s hard – but that is why we practice. To return again and again to what is actually happening and respond from that ground – the ground of zazen.

We stand to lose a lot of what we think of as certain. We risk losing our most cherished opinions of ourselves and others. And we might even lose – if we’re lucky – what we’ve spent so long constructing – our fixed sense of self.

All of this, just by sitting on a little black cushion.

So, what a dangerous place you’re sitting in!

I want to finish by observing that the governor originally offered these words as challenge to the priest. But instead of besting his opponent he was given a radical way to practice these words instead. His challenge was turned completely around

The dialogue between governor and priest inevitably transcends sacred and profane, affirming shared reality in the process.

We’re told that in gratitude for this humble, demanding and elegant teaching, the governor simply “bowed and departed.”

I can only do the same, wishing you well.

This talk was originally given at the Mountains and Rivers Zen Group Sesshin in 2017